Dhamma explorations

INTRODUCTION

These pages feature articles and shorter items recording investigations into the teaching of the Buddha by groups and individuals.

'Dhamma' can be interpreted in several ways, meaning for example, 'the teaching of the Buddha' or 'the truth'.

The contributions mostly concern matters related to samatha-vipassanā practice and the Therevāda tradition but are by no-means limited to these.

Previous articles

The Eight Worldly Conditions - an investigation

The Four Foundations of Mindfulness - an investigation

HAIKUS FOR MEDITATORS

The Haiku is a form of poetry that originated in Japan. Expressed in English, the Haiku is non-rhyming and comprises three lines of five, seven and five syllables respectively, seventeen syllables in total. The format is often used as a creative way to reflect on aspects of the natural world and their connection with the human heart and mind.

The following Haikus were composed by Samatha members who took part in a celebration of Dhamma Day on 24th July 2021 at the Manchester Centre for Buddhist Meditation. Dhamma Day marks the occasion when the Buddha gave his very first teaching, including the Middle Way, the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path

The day coincides with the full moon and poems were therefore based on this theme, so might be called ‘Lunar Haikus’.

(Asalha Full Moon Haiku)

rose moon reflected

in the petals of the apple

tree I sit under

---------------------------

(Winter Moon Haiku)

quiet Wolf moon rests

wrapped in velvet blanket

of infinite space

---------------------------

My favourite moon appears

On a cold night winter sky

Looped in a rainbow

----------------------------

(Summer Moon)

Still summer evening

The moon is a nimitta

Promising coolness

(Autumn Moon)

Clinging to tree tops

Radiance hidden. Then free,

In vast open sky.

----------------------------

Winter walk home

The brightest whitest moon

Lights our way

Through the window

Shines the full bright moon

Casting a shadow

----------------------------

Full moon clearly seen

Bright in a Manchester sky

Most unusual!

----------------------------

Out of the sea like

A reverse sunset. Breath caught.

It rises silver

Out of the sea like

an orange balloon; rising

Rising to stillness

---------------------------

When I crane my neck,

hold on to the windowsill-

I just can see this full moon

I know it is there,

behind the tree,

just above the roof...

The sphere of the moon

seems to lighten up

the airless space around it

Just knowing it is up there

brightens up this night

MINDFULNESS AND CONCENTRATION

Mindfulness (sati)

Buddhism is perhaps unique in its emphasis on this quality – though in recent years, aspects of it have been taken up in Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction and Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy. The second of these secular therapies has been recognised by the UK National Health Service as an effective means to prevent people who have suffered from depression from relapsing back into it by being drawn into negative thought patterns.

Buddhism sees mindfulness as a crucial aspect of the process of meditatively calming down and waking up so as to see things as they really are. Both of these help us to reduce the suffering that we inflict on ourselves and others. As is said by the Buddha in his Discourse on the Applications of Mindfulness (Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta), mindfulness is ‘the direct path for the purification of beings, for the overcoming of sorrow and lamentation, for the ending of pain and unhappiness, for acquiring the true method, and for experiencing Nirvana (the end of greed, hatred and delusion)’.

To be mindful is to be clearly aware of what is experienced in the present moment, being present with, and paying careful attention to, the wondrous flow of here … now. When we stand back from and alertly take stock of what we are thinking, feeling and doing, this allows things to naturally calm down. We are then open to experiencing a dropping away of normal mental horizons and limitations, a kind of timeless presence, with feelings of happiness and ease.

When we have developed more mindfulness, we tend to more easily notice simple natural events in the environment, such as a leaf gently falling to the ground, or ripples on the surface of a river or pool, or a trickle of rain running down a car windscreen while one waits in traffic. Mindful observation of these can allow a natural delight to arise…

Mindfulness is mind-ful-ness: full presence of mind, alert attention, mental clarity, being wide awake, fully with-it, vigilant, not on auto-pilot. During a normal day, much of the time we are operating on auto-pilot, involved in habitual actions and thought patterns. It is a bit like when rice pudding starts to cool, and gets a skin on it: a congealed barrier between it and the air. But when mindfulness arises, we are more alive and alert; something switches on that was previously inactive

Mindfulness is a thorough observation which is not careless in its watchfulness: it sees things as they are, without overlooking aspects of them, or projecting things onto them. It is also disinterested and non-judgemental, observing, without reacting for or against; a ‘bare attention’ that simply notes and registers what is going on, a full awareness of what is happening in and to us, as it happens – the aspect emphasised in secular forms of mindfulness.

Mindfulness also has an aspect of memory to it. It remembers what one is supposed to be attending to, so one does not ‘float away’ from it; and if the mind has wandered off, it reminds one to return to the focus of meditation. It is also used when one has undistorted memory of a past experience, especially of meditative experience and its beneficial qualities, so as to not lose one’s connection to these, and help them arise now.

An important fruit of mindfulness is that it conduces to a simple, natural, non-habitual state, in which things ‘flow’ better.

In particular, mindfulness of breathing takes a look at something seemingly very ordinary, always under one’s nose. It is the steady watching and clear awareness of a smooth breath – a natural flowing, if not at its normal length – particularly noting its length, and clearly noting the flow of sensations and related feelings. This allows one to feel what it is actually like, rather than just thinking about it: as if feeling it for the first time.

Its quality of careful observation helps one not be confused about the breath, and its quality of alertness prevents ‘switching off’ from the breath into a dull ‘staring’ attitude, as when the mind stops taking things in when reading.

It remembers that the aim is to stay with the breath in the present moment, so it guards against losing concentration and switching away from the breath, wandering away into the past, future, daydreams, worries, sleepiness ....

It carefully notices when attention nevertheless wanders onto such things, so that it can be gently brought back to the breath, so as to again mindfully feel it and know where one is in the process.

If annoyance arises in the mind, whether directed at one’s own wandering mind, external noises, or their source, mindfulness recognises this, but helps one step back from involvement in the irritation, so one can let go of it and return to the breath. The same applies, for example, with any anxiety on ‘am I doing this right?’.

Once the slow deep breathing has been established, mindfulness observes it without interference, so one can let the breath be, and not be anxious, as one nears the end of the in-breath, about when the out-breath will start, or vice versa; it will happen naturally.

When one has finished a meditation ‘sit’, it is good to mindfully recollect how it went. Mindfulness can also be used during the day, either to periodically notice what the breath is doing or how the mind is reacting. One can pause to check out how one feels: feeling one’s contact with the ground through the feet, noting any tensions in the body. Then note one’s emotional state. Mindfulness is a patient, kindly observation, which gives space for things to be what they are, and then to gradually change and pass. This is very helpful when applied, for example, when one feels low, or irritated, or worried, or afraid … It helps one to acknowledge these states, but then to let go of them.

Concentration, or mental unification (samādhi)

People’s normal experience of ‘concentration’ usually varies from a half-hearted paying attention, to becoming absorbed in a good book, when most extraneous mental chatter subsides. Buddhist meditation, in common with many other forms of meditation such as Hindu yoga, aims to cultivate the power of concentration till it can become truly ‘one-pointed’, with 100 per cent of the attention focused on a chosen calming object. In such a state, the mind becomes free from all distraction and wavering, in a unified state of inner stillness: mental unification.

In meditation, ‘concentration’ refers not so much to the gentle effort of concentrating – though this is also needed – as to the state(s) of mental unification that this leads to. Samatha teacher Sarah Shaw says:

"The word concentration does not necessarily mean the kind of rigid application of mind that occurs when the maths teacher at school enjoins us to ‘concentrate!’ Here it is more akin to its earlier English sense of bringing together, as in a concentrate. Samādhi is like a pooling of the resources of the mind when faced with a pleasing and intricate problem, that absorbs all one’s interest – a state which interest in a mathematical problem can bring of course, or working out and digging a rock garden. Attention is governed not so much by one’s own effort, but by the object itself, which changes and influences the nature of the mind that considers it. The object starts to be perceived without ‘wanting’ or rejection, but for its own sake. This is the kind of concentration which, according to the abhidhamma [Buddhist systematic psychology] can and indeed is in a small part present in daily consciousness. When this is developed in jhāna [deep meditation], the mind is made unified and one-pointed, capable of seeing without distractions or hindrances."

Concentration yokes the mind onto an object or project, be this good, bad or indifferent. It is a state of being focused, whatever the level of one’s alertness/awareness. It is possible to be quite focused, but not very aware/mindful: e.g. Sir Isaac Newton boiling his watch instead of an egg, when concentrating on an intellectual problem. It is possible to be very mindful without necessarily focusing on any one object, though if there is good mindfulness, this makes concentration easier. When concentration is combined with mindfulness, and focused on a simple object such as the breath, it becomes ‘right concentration’, and integrates the mind’s energies so as to bring about mental stillness, tranquillity and peace: a quiet yet positive state of mind.

Right concentration is a wholesome one-pointedness of mind: a wholesome state of mind steadily focused on a calming object. It is an intensified steadiness of mind, a state where the mind is like a clear flame burning in a windless place, or the surface of a clear, undisturbed lake.

It is a state of steady focus, mental composure and stillness, which unifies and harmonises the mind’s energies, as when a class of children are all intently listening to a good teacher, not fidgeting or looking out of the window. It is experienced as a state of tranquillity and clarity, and comes about when there is a state of happiness that allows the mind to contentedly stay on the object, as one has developed a natural interest in it.

In meditation on the breathing, mindfulness establishes a link between the mind and the breath, knowing its length and how it feels, while concentration is the state of being well-focused on the sensations known by mindfulness, aided by the counting. At any time in the meditation, mindfulness will give awareness of:

- the length of the breath, its speed, smoothness, and whether it is an in or out breath.

- the subtle sensations which arise along the path of the breath, and subtle feelings that come when one attends carefully to the flow of the ‘breath body’.

- where one is in the process, such as the stage of practice one is in, and what one is supposed to be doing.

- aspects of posture that may need re-tuning.

- whether the mind has wandered.

Concentration is the quality of remaining generally focused, ‘centred’, on the breath, hopefully including the sensations in a particular part of the path of the breath as one scans along this. At first, this is particularly aided by attention to the numbers one is counting as one breathes. The counting aids both mindfulness and concentration.

When the mind wanders, this is because, first of all, mindfulness slips, and one forgets what one is supposed to be doing. Concentration is then lost, as the mind becomes distracted, and loses its focus. If one then becomes involved in a long wandering thought, there may be concentration on this, but no mindfulness. When one notices that the mind is not on the breath, this marks the return of mindfulness, which then allows one to re-establish awareness of the breath, then concentration on it.

The practice starts to work well when there is a balance of a high degree of both mindfulness and concentration, so as to bring about a state of alert stillness.

THE HINDRANCE AS IMAGES

One of the first things someone new to samatha meditation learns, after going through the structure and technique if the practice, is to be aware of the hindrances.

(Experienced meditators also need to maintain this awareness and continue their efforts to overcome hindrances whenever they arise on the meditation journey.)

Hindrances are things that create obstacles to meditation, that weaken attempts to calm the mind and hinder the process of mental concentration. In Buddhist teachings, five hindrances are identified:

Sense desire, or desire for pleasure arising from sights, sounds, smells, tastes or forms, which can range from subtle liking to powerful lust.

Ill will, or aversion towards people, things or experiences, which can range from mild annoyance to powerful hatred.

Sloth and torpor, or mental dullness, inertia or drowsiness.

Restlessness, in the form of agitation or disquietude, sometimes referred to as ‘flurry and worry’.

Doubt, which is uncertainty or questioning of the practice, the process or the teaching.

To aid understanding, the Buddha used the simile of a bowl or a pool of water, which is essentially pure and clear and in which a man can see his reflection as it really is. The hindrances represent five ways in which the water can be disturbed or contaminated, thereby distorting the reflected image.

Sense desire – the water is mixed with brightly coloured paints.

ill will – the water is boiling.

Sloth and torpor – the water is covered by a mossy film.

Restlessness - the water is rippled by the wind.

Doubt – the water is muddied

The question that arises from this is, what can we do about it? How can we avoid or overcome the hindrances in order that our meditation practice can be as still and clear as the water before it was disturbed?

The answer is through the five faculties, or cardinal virtues, the development of which lie at the heart of meditation practice, and which are normally listed in this order:

- Mindfulness

- Faith, or Confidence

- Effort, or Energy

- Concentration

- Wisdom

When ‘matched’ to the hindrances, the faculties are ordered to indicate which faculty is most effective in overcoming which hindrance:

HINDRANCE FACULTY

Sense Desire Mindfulness

Ill will Faith/Confidence

Sloth & Torpor Effort/Energy

Restlessness Concentration

Doubt Wisdom Wisdom

Perhaps by reflecting on this for a while, by recalling it when hindrances arise during meditation practice, and in particular by recalling the images of disturbed water, we can see the hindrances for what they are and recognise the way in which the faculties can work to overcome them.

Developing the faculties then becomes part of the process of developing the meditation, working individually, with one’s teacher and with one’s Sangha group. It is also important to remember the way the faculties should be balanced: faith balanced with wisdom, effort balanced with concentration, with mindfulness at the centre or encircling the others.

As the hindrances fade away the mind becomes more settled, just as the water returns to its natural state of stillness and clarity.

EVERY BREATH YOU TAKE

It’s said that we breathe on average about 20,000 times a day, including when we’re asleep. In normal waking hours, that amounts to about 110,000 times a week, getting on for 6 million times a year. Based on an expected lifespan of 80 years, that’s an ‘allowance’ of around 480 million combined in- and out-breaths we might expect to take in an average Western lifetime.

Looked at in these terms, the number of breath-watching opportunities available to most of us in a normal life is vast. So the question that might arise for meditators wishing to embrace the notion of moment-to-moment mindfulness is this:

How many of those breaths are we, or have we been, conscious of or awake to as they happen? How many have gone by, how many are yet to come?

We don’t need to work these answers out, neither do we need to regret the past or question what we might be capable of in the future. In any case, a single breath can only ever occur in the present.

Rather let it serve simply as a reminder that time is always passing by, and the opportunity is always there to be more attentive at any moment to everything that’s within us and around.

This is clearly the reason that the Buddha directed us to meditate by observing the breath. In the Satipattāna Sutta, emphasising the sheer simplicity of watching the breath, he describes the process to be followed by the listening monk:

"Mindful, he breathes in, and mindful, he breathes out. He, thinking, 'I breathe in long,' he understands when he is breathing in long; or thinking, 'I breathe out long,' he understands when he is breathing out long; or thinking, 'I breathe in short,' he understands when he is breathing in short; or thinking, 'I breathe out short,' he understands when he is breathing out short.”

The breath is always there, as long as there is life. We begin by observing the breath when we sit to meditate. We learn to control its length and apply techniques of concentration that are synchronised with the breathing.

When the mind gets distracted, we re-focus it by bringing attention back to the breath. So the breath and awareness of breathing are crucial to the whole process of meditation, as they are to the business of awakening in everyday situations.

Given that ‘everyday situations’ make up most of the time available to observe the breath, the challenge is then to find ways to wake up and be present to as many of those moments as we can – to remember to remember the breath!

So how do we do this? Every meditator will have been given suggestions by their teachers, or picked them up in group meetings over time, so here are some reminders:

- Notice every time you walk through a door

- Notice whenever you pick up a familiar object such as a cup to make a drink

- Observe your actions when you do something habitual, like sitting down to eat

- Pay attention at the start of an activity, such as turning the ignition key in a car, and aim to avoid the experience of driving a journey only to have no detailed memory of it at the end!

- When talking to another, watch them more closely and listen more carefully

- Pause deliberately before engaging in a task like switching on a computer or mechanical device

- Try to catch the moment before answering a phone or opening the door to a visitor

Many more actions and activities like these are available to us every day. They all involve use of the senses, which makes awareness of what we are seeing, hearing, touching etc. vital. And they all give us the opportunity to awaken, remember, and go to the breath. Then having reconnected with the breathing, to try and maintain that connection.

The millions of available breaths mentioned at the start of this article may sound like an abundant store, but that store becomes depleted with every passing hour. The life expectancy quoted at the start is an average and nothing is guaranteed. None of us knows much longer this present life will last. As we were advised by Ven Walpola Rahula in the following extract from his classic text “What the Buddha Taught”, the time to observe the breath is now!

“Whether you walk, stand, lie down or sleep, whether you stretch or bend your limbs, whether you look around, whether you put on your clothes, whether you talk or keep silence, whether you eat or drink, even whether you answer the calls of nature – in these and other activities, you should be fully aware and mindful of the act you perform at the moment. That is to say, you should live in the present moment, in the present action”

THE ELEMENTAL SELF

INTRODUCTION

Ayya Khema was a German-born Buddhist nun, teacher and author who among many other achievements set up the International Buddhist Women’s Centre and Parappudua Nuns’ Island in Sri Lanka. She was spiritual director of Buddhaus retreat centre in Germany, and her numerous publications include ‘Being nobody, going nowhere’ and ‘Who is my self?’ Many of her talks and articles are available at www.accesstoinsight.org .

The following is an edited version of Ayya Khema’s dhamma talk “Contemplation on the Four Great Elements” and is reproduced with permission of Buddha-Haus, Germany, © Buddha-haus (buddha-haus.de).

The article includes a meditation on the four elements.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Everything consists of the four primary elements: earth, fire, water, and air. Observing the presence of all four of these elements within us, or even just one of them, can be an important way of recognizing how our individual composition is the same as the composition of the rest of the universe. This may be an intellectual understanding at first, but eventually, with practice, it can become a feeling—one of being exactly the same as everything around us.

Anything that we can touch has the earth element: our body—our flesh, bones, and hair; the ground; even water. We humans, reliant as we are upon what we can see and touch are most concerned with this earth element, particularly as it relates to the body. The body should have the right shape, the right colour, the right age, and the right abilities. But really our bodies are nothing more than an assortment of components that are found throughout the universe.

The fire element indicates temperature—warm or cold—and the capacity to digest or to eat. Our margin of comfort for internal temperatures— between 60 and 80 degrees Fahrenheit—is rather small. According to some Buddhist traditions, however, we can expand our comfort level and open ourselves up to the realization that our body contains all temperatures.

The water element implies not only water but also blood, urine, sweat, tears, and so on. It’s also the binding element: it makes things hang together. If you add water to flour, for instance, you get dough. Adult human bodies are composed up to 60 percent of water; if they weren’t, the cells would probably wander around separately, because there would be no binding element.

And last but not least, the air element refers to the body’s breath, wind, and movement. Whenever we move, it’s as though the wind has taken over. Even when we walk, we can see that we are dispersing air and creating movement, however subtle.

When we meditate on these four primary elements in ourselves and in the outer world, we no longer feel threatened by external forces or situations, because we recognize that everything, and everyone, is composed of these same four elements. We see that there are no distinctions between one and the other, and are thereby able to realize the complete oneness of existence and manifestation. Without the feeling of separation from the rest of the world, we also lose the need to strain and stress to be better, more clever, or more accomplished. We can start to just be. That’s all there is to it.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Here’s how to practice meditation on the four elements:

First, put your attention on the breath for just a moment.

Then, feel the solidity—the earth element—of your body. Touch your hands or your knees, or feel your mouth where the lips meet. Feel the bones throughout your body, the skin above them, and notice the subtle pressure of the eyelids on the eyes.

Let that feeling of solidity flow into and merge with the earth element of the cushion that you sit on. Then become aware of the earth element in the soles of your feet and in the floor or mat. Again, let the two earth elements merge.

Now imagine that you are going to walk outside. With each step that you take, the earth element in your feet merges with the earth element of the floor you walk on. You walk to the door, and as you put your hand on the doorknob, the earth element in the palm of your hand merges and flows into the earth element of the door, which you now open.

Imagine walking outside, your feet merging with the literal earth beneath you. You walk over to the nearest tree and lean back against its trunk, allowing your body to merge with its solidity. No separation.

Visualize yourself continuing to walk outside and coming upon a stream. You put your hand into the stream and feel the water’s solidity pressing against your fingers, recognizing that this solidity is what allows boats to float and fish to swim.

You look up at the sky and let your body’s earth element flow into the clouds, which have their own solidity. There’s no division, no separation—only merging. To one side you see a friend, whose body also contains the earth element, and you both observe that shared experience.

Now come back to your immediate surroundings and return to the breath. In this second exercise, focus your awareness on the temperature in your body. Some parts may be warm; other parts may be cold. What is the temperature of the cushion or chair you’re sitting on? In the same way as before, let the two—the warmth or coolness in yourself and in your seat—merge together. Do the same with your feet on the floor. Become aware of the temperature in the soles of your feet and the temperature of the floor. Let them become one.

Go through the same imagination exercise as before—walking to the door, going outside, leaning against the tree, touching the water, looking at the sky, and seeing a friend—but do so with your focus placed on the fire element. Feel the temperature of the earth, the water, and the sunshine in the air. Imagine going into the shade, and how that changes your interaction with fire. The coolness touches your body and generates feeling. The shade and you yourself are not separate.

Now go to the nearest tree and touch it with your hand, feeling its temperature. Merge your own feeling of warmth with the warmth of the tree, and realize that you’re no longer separate from that tree. Imagine leaning back against the tree, absorbing the warmth from the sun’s rays or the coolness of the shade and tuning into the fact that you and the tree share the same fire element in the form of temperature.

For each of the two remaining elements, water and air, repeat the steps outlined above, always first tuning into the breath, then focusing in turn on the element of water and air in the body, then imagining yourself navigating the external world of elements. All the while, recognize that you share the experience of that element with everything you encounter—the wet morning dew; dry, crackly leaves; birds zooming through the air; clouds drifting above. Use your sensory imagination to weave a rich tapestry of connection.

With practice, one day we will recognize that all phenomena are composed of and dependent upon the interaction and merging of these four elements. We will realize that all of it—the entire universe—is just one continuous manifestation. And that we, ourselves, are no different.

THE FOUR FOUNDATIONS OF MINDFULNESS

AN INVESTIGATION BY MEMBERS OF THE WILMSLOW GROUP AND OTHERS, SPRING 2020

INTRODUCTION

The group dedicated its weekly meetings over an extended period to exploring the topic of mindfulness, based on the Satipatthāna Sutta. The regular members of the group were augmented by some meditators connected to other groups.

The work was guided by a text written by Sri Lankan monk and author Bhante Gunaratana Henepola, entitled ‘The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English’.

Members of the group were encouraged to investigate each aspect of the four foundations in a practical way, by observing their everyday experiences and reporting their findings.

The project started with normal meetings a few weeks before the arrival of the coronavirus problem, and continued online to its conclusion. This had an effect on the nature of the proceedings, not least by ensuring 100% attendance once it went virtual!

At the end of this document there is a link to a summary of presentations made at the end of the course, showing individuals’ reflections and conclusions in written, pictorial or diagrammatic form.

SUMMARY

The four foundation of mindfulness are:

1. Mindfulness of the body

2. Mindfulness of feelings

3. Mindfulness of mind

4. Mindfulness of Dhamma

In more detail, each of the four foundations in turn comprises:

• Body – the breath, the four postures, mindfulness with clear comprehension, reflection on the 32 parts of the body, the four elements and the nine cemetery contemplations.

• Feelings – pleasant, unpleasant or neutral, as experienced through sensations or emotions.

• Mind – greedy or not greedy, hateful or not hateful, deluded or not deluded, contracted or distracted, not developed or developed, not supreme or supreme, not concentrated or concentrated, not liberated or liberated.

• Dhamma – the five hindrances, the five aggregates of clinging, the six internal and six external sense bases, the seven factors of enlightenment, the four noble truths and the noble eightfold path.

INVESTIGATION

Following contemplation, practical investigation and discussion at each stage of the course, understanding and insights arose in various ways. A full record of the course’s progress would be too lengthy to reproduce here, so a selection of the more outstanding points is given. Quotations are from the text.

MINDFULNESS

“In Pāli, the word for ‘to remember’ is sati, which can also be translated as ‘mindfulness’”.

The word ‘mindfulness’ is very familiar to Samatha meditators, and can be interpreted in many ways – awareness, presence, awakening, in-the-moment consciousness, etc. The common experience seems to be that we can only practise mindfulness when we remember to – we need to remember to remember!

Various techniques can be deployed to do this, most commonly associated with the body and the senses. Examples are noticing and more closely observing the objects we handle, paying closer attention to routine activities like preparing and eating food, and being more attentive to our interactions with other people, particularly speech and body language (Right Speech being one stage of the Noble Eightfold Path).

In the context of the coronavirus situation, the acts of handwashing and avoiding contact with the face had immediate relevance.

MINDFULNESS OF BODY

“The only place and time truly available to us is right here and right now. For this reason, we establish mindfulness by paying attention to this very instance of breathing in and breathing out.”

Mindfulness of the body begins with mindfulness of the breath, and from this very simple, constantly occurring phenomenon, a multitude of connections arise.

The five faculties (indriya) – faith balanced with wisdom, effort balanced with concentration, and mindfulness connecting all of these – all feature in the process of watching the breath.

The five aggregates (khandas) – form, feeling, perceptions, mental formations and consciousness – also come into play.

The four elements are present in the breath – earth in the physical body that breathes, water in the breath’s fluidity, air in the breath’s movement, fire in the breath’s energy and temperature.

Throughout, there is impermanence (anicca). The quality of breath is ever changing; we breathe around 18,000 times each waking day and no single breath is ever the same.

Meditators found it helpful to be reminded of the importance of correct posture in sitting, and to give renewed attention to standing and walking practice.

The sutta also refers to mindfulness with clear comprehension, which cuts across all the aggregates and which can be applied most easily in everyday activities such as eating – watching how much we eat, how quickly, our composure, and avoiding simultaneous activities and mental distractions while eating.

MINDFULNESS OF FEELINGS

“When we are attached, even pleasantly so, we are not mindful, and thus we are vulnerable to suffering. When we are free from desire, although the entire universe continues to change, we do not suffer.”

In the Buddha’s teachings, feeling (vedanā) includes both physical sensations and mental emotions, and each can be pleasant, unpleasant or neutral. The three kinds of feeling can be experienced through any of the six senses, which include the mind, giving eighteen possibilities, and these can all arise as physical sensations or internally generated emotions, making thirty-six variations. Applied to past, present and future, a total of 108 kinds of feelings can be distinguished!

Feelings arise initially from sense contact, but it is at the point where mental perceptions, interpretations and reactions occur that skilfulness is most needed. Sights and sounds may enter the senses, but it is mental activity that turns them into upsets, annoyance or anger. For this reason we are advised to ‘guard the sense doors’; applied mindfulness is the key to ensuring that when feelings arise they do not automatically lead to negative responses.

MINDFULNESS OF MIND

“Whatever thoughts we cultivate frequently become a habit.”

The sutta refers to consciousness, and we usually speak of the activity of the mind simply as ‘thoughts’. The Buddha warned his monks to avoid too much thinking, saying ‘when the mind is strained it is far from concentration’, and advised them to meditate.

Attempting to control the mind and its constant flow of thoughts is part of the process of meditation and for most it is a difficult struggle, often compared to the attempt to control a wild animal, such as a tiger, elephant or monkey.

The best results tended to come from a more detached, accepting approach that recognises this difficulty and works patiently with simply observing and noting thoughts as they occur. More peaceful outcomes came by remembering not to follow or resist thoughts and by recognising that, like all phenomena, thoughts are impermanent and pass away with time.

Recalling and practising the divine abidings ( Brahma Vihāras ) became very important in this context. The need to apply loving kindness (metta), compassion (karunā), sympathetic joy (mudita) and equanimity (upekkhā) towards oneself proved most helpful in maintaining the effort to deal with thoughts, both during meditation practice and in everyday life.

MINDFULNESS OF DHAMMA

“It takes outstanding qualities of mind and heart to reach our spiritual goals …. Our task is like preparing a plot of ground to grow a garden.”

‘Dhamma’ can be interpreted in various way such as ‘the teachings’, ‘truth’ or ‘phenomena’. In the sutta it is given as ‘contemplation of mental objects.’ Foremost here are the five hindrances – sense desire, ill will, sloth & torpor, agitation and doubt. These are well known to every meditator, but a period of closer examination on this course threw up many new realisations. In the simile given in the quotation above, removing the hindrances is akin to removing weeds and obstructions on the surface of the ground.

The hindrances here are followed by the five aggregates of clinging, meaning identification with the khandas as ‘my body, my feelings’ etc. Clinging to these ideas means attachment to the idea of a permanent self, specifically denied by the teaching of anatta. Continuing the simile, abandoning the idea of self allows us to start digging and uproot anything that will impede wholesome growth.

Mindfulness of Dhamma in the sutta and in the text ends with contemplation of the seven factors of enlightenment and the four noble truths, the last of which being the noble eightfold path. Completing the garden analogy, this is seen as the point where understanding and wisdom can begin to grow.

They are clearly major areas of study within themselves, deserving further investigation over future courses and remaining lifetimes!

WORD OF THE WEEK (WOW)

Throughout the course a single word was chosen most weeks, resulting either from experiential findings or discussions around a particular topic. These led to further insights and opportunities to examine skilful and unskilful behaviour.

Proliferation : the tendency of the mind to extend one thought into another, inventing and imagining further ‘stories’ from a single notion.

Mechanical : the tendency to react automatically and repeatedly to events in a similar way, and looking to catch these moments at the point where they occur.

Watching : developing the ability to observe events ‘from outside’, thereby helping avoid unskilful speech or actions.

Experience : what does it means to ‘have’ an experience, to ‘be’ experienced, or to ‘learn from’ experience?

Touch : as part of mindfulness of feelings, noticing how the senses operate, the feelings that then arise and the way the mind interprets them, focusing on the sense of touch.

Habit : noticing (retrospectively) the absence of mindfulness – which might be called ‘mindlessness’ – when we ‘default’ to habitual behaviour, and the challenge of bringing about change.

Clarity : through clear comprehension, the path towards purifying the mind, ending suffering and attaining liberation.

Conclusion : bringing a period of group work to an end. Recollecting, reviewing, ‘banking’ what has been learned. Continuing to ‘strive on’.

Gladness : recognising good fortune, the benefits of working together and the value of such opportunities to develop skilful behaviour.

CONCLUSION

At the end of the course, participants presented their findings in various different formats. Several speak for themselves, others include commentary based on oral contributions delivered at the time.

Follow this link to view these presentations:

The Four Brahma Vihāras

At a time of great fear and anxiety, it may be comforting to ‘go back to basics’ and reflect on one of the Buddha’s most fundamental teachings.

The Brahma Vihāras (sublime states, or divine abidings) are four qualities that remind us of our common humanity and the importance of purifying the heart.

The qualities are Mettā, loving kindness, Karunā, compassion, Muditā, sympathetic joy, and Upekkhā, equanimity. The first three relate directly to the way we connect with other living beings, while the last in an internal process that indirectly pervades all aspects of our external behaviour.

There could be no better guidelines to help us through difficult times.

The Basic Passage on the Four Sublime States from the Discourses of the Buddha

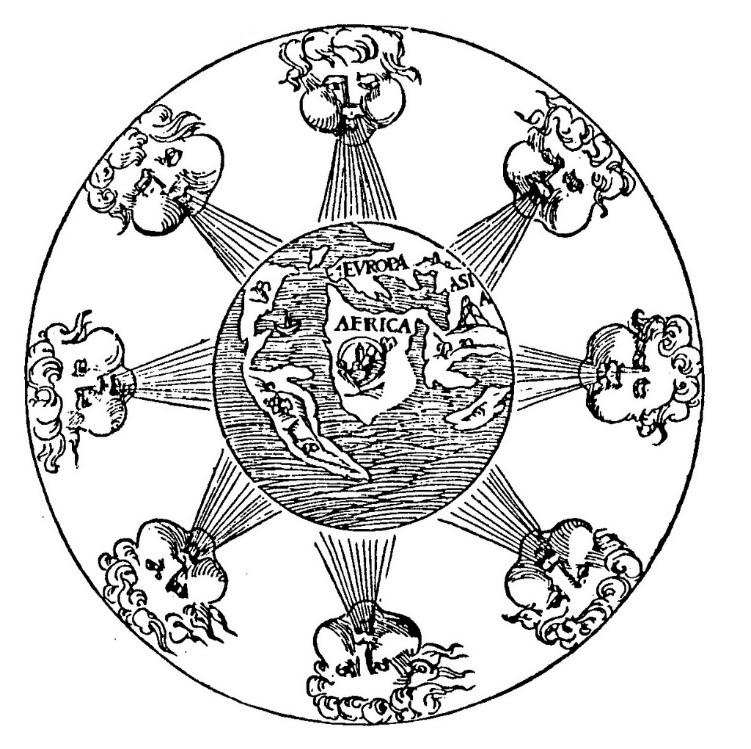

I. Here, monks, a disciple dwells pervading one direction with his heart filled with loving-kindness, likewise the second, the third, and the fourth direction; so above, below and around; he dwells pervading the entire world everywhere and equally with his heart filled with loving-kindness, abundant, grown great, measureless, free from enmity and free from distress.

II. Here, monks, a disciple dwells pervading one direction with his heart filled with compassion, likewise the second, the third and the fourth direction; so above, below and around; he dwells pervading the entire world everywhere and equally with his heart filled with compassion, abundant, grown great, measureless, free from enmity and free from distress.

III. Here, monks, a disciple dwells pervading one direction with his heart filled with sympathetic joy, likewise the second, the third and the fourth direction; so above, below and around; he dwells pervading the entire world everywhere and equally with his heart filled with sympathetic joy, abundant, grown great, measureless, free from enmity and free from distress.

IV. Here, monks, a disciple dwells pervading one direction with his heart filled with equanimity, likewise the second, the third and the fourth direction; so above, below and around; he dwells pervading the entire world everywhere and equally with his heart filled with equanimity, abundant, grown great, measureless, free from enmity and free from distress.

— Dīgha Nikāya 13

Brahma Viharas Meditation Practice

Generally speaking, persistent meditative practice will have two crowning effects: first, it will make these four qualities sink deep into the heart so that they become spontaneous attitudes not easily overthrown; second, it will bring out and secure their boundless extension, the unfolding of their all-embracing range.

In fact, the detailed instructions given in the Buddhist scriptures for the practice of these four meditations are clearly intended to unfold gradually the boundlessness of the sublime states. They systematically break down all barriers restricting their application to particular individuals or places.

In the meditative exercises, the selection of people to whom the thought of love, compassion or sympathetic joy is directed, proceeds from the easier to the more difficult. For instance, when meditating on loving-kindness, one starts with an aspiration for one's own well-being, using it as a point of reference for gradual extension: "Just as I wish to be happy and free from suffering, so may that being, may all beings be happy and free from suffering!" Then one extends the thought of loving-kindness to a person for whom one has a loving respect, as, for instance, a teacher; then to dearly beloved people, to indifferent ones, and finally to enemies, if any, or those disliked. Since this meditation is concerned with the welfare of the living, one should not choose people who have died; one should also avoid choosing people towards whom one may have feelings of sexual attraction.

After one has been able to cope with the hardest task, to direct one's thoughts of loving-kindness to disagreeable people, one should now "break down the barriers (sīmā-sambheda)". Without making any discrimination between those four types of people, one should extend one's loving-kindness to them equally. At that point of the practice one will have come to the higher stages of concentration: with the appearance of the mental reflex-image (patibhāganimitta), "access concentration" (upacāra samādhi) will have been reached, and further progress will lead to the full concentration (appāna) of the first jhāna, then the higher jhānas.

For spatial expansion, the practice starts with those in one's immediate environment such as one's family, then extends to the neighbouring houses, to the whole street, the town, country, other countries and the entire world. In "pervasion of the directions," one's thought of loving-kindness is directed first to the east, then to the west, north, south, the intermediate directions, the zenith and nadir.

The same principles of practice apply to the meditative development of compassion, sympathetic joy and equanimity, with due variations in the selection of people.

The ultimate aim of attaining these Brahma-vihara-jhanas is to produce a state of mind that can serve as a firm basis for the liberating insight into the true nature of all phenomena, as being impermanent, liable to suffering and unsubstantial. A mind that has achieved meditative absorption induced by the sublime states will be pure, tranquil, firm, collected and free of coarse selfishness. It will thus be well prepared for the final work of deliverance which can be completed only by insight.

The preceding remarks show that there are two ways of developing the sublime states: first by practical conduct and an appropriate direction of thought; and second by methodical meditation aiming at the absorptions. Each will prove helpful to the other. Methodical meditative practice will help love, compassion, joy and equanimity to become spontaneous. It will help make the mind firmer and calmer in withstanding the numerous irritations in life that challenge us to maintain these four qualities in thoughts, words and deeds.

On the other hand, if one's practical conduct is increasingly governed by these sublime states, the mind will harbour less resentment, tension and irritability, the reverberations of which often subtly intrude into the hours of meditation, forming there the "hindrance of restlessness." Our everyday life and thought has a strong influence on the meditative mind; only if the gap between them is persistently narrowed will there be a chance for steady meditative progress and for achieving the highest aim of our practice.

Meditative development of the sublime states will be aided by repeated reflection upon their qualities, the benefits they bestow and the dangers from their opposites. As the Buddha says, "What a person considers and reflects upon for a long time, to that his mind will bend and incline."

The Eight Worldly Conditions

Investigating the nature of Upekkha

INTRODUCTION

In the autumn term of 2018, a group of meditators from various local classes met at the Manchester centre to explore the titular subject over a six-week period.

The Eight Worldly Conditions (sometimes known as Winds or Vicissitudes) were first promulgated by the Buddha in the Lokavipatti Sutta, translated* as “The Failings of the World”. They are named as four pairs of opposites:

• Gain and Loss

• Status and Disgrace

• Censure and Praise

• Pleasure and Pain

The sutta begins by declaring that the eight conditions “spin after the world, and the world spins after them”, which is a way of saying that human life is caught up constantly in them in virtually everything we do. The winds may blow favourably or fiercely – in our perception at least – but they never stop blowing, so everything depends on the way we respond to this metaphorical weather.

The point of the sutta is made clearly and concisely by contrasting the responses of the “uninstructed, run-of-the-mill person” and the “well-instructed disciple of the noble ones” to each of the eight conditions as they arise. It says that the difference between these responses comes down to one thing: the ability to recognise the conditions as “inconstant, stressful and subject to change” – and deal with them accordingly – or not.

As we might expect, the “uninstructed” one fails to discern wisely, instead choosing to welcome the desirable qualities and rebel against the undesirable ones, whereas the “well-instructed” one treats them with equanimity. The former is not released from suffering, the latter is, and “goes beyond.”

The focus of the group was therefore on exploring everyday experiences, during the progress of the course or in recent memory, in order to discern whether these events and their consequences could be seen as “inconstant, stressful and subject to change” in practice, and thereby result in changes to habitual responses. (Many meditators will recognise these three descriptions in other terms as the three signs or characteristics of being, viz. anicca, dukkha, anattā, or impermanence, suffering, not-self.)

PREPARATION

It was clear that the quality of Upekkhā (Equanimity) would be central to any exploration of the eight conditions, and that equanimity in turn needed to be viewed in the context of its presence as one of the four Brahma Vihāras (Divine Abidings), viz. Mettā (Loving Kindness), Karunā (Compassion), Muditā (Sympathetic Joy) and Upekkhā (Equanimity).

The order in which these are given is significant in that Mettā is foremost, needing to be practised firstly towards oneself and then towards others. In this investigation, it was seen as crucial to the process of self-examination, particularly in what might be difficult or challenging situations or recollections. Mettā practices were therefore incorporated in the course and participants were advised to maintain Mettā practices and awareness during their investigations.

Upekkhā is given as the fourth Brahma Vihāra since it can be seen as the result of developing the other three, and to incorporate them. The Pali translation is ‘looking over’ meaning to see without being drawn in to what we see. It should not be confused with its “near enemy”, which is indifference, and is best described in the concluding words of the Sutta, where it says:

“The wise person, mindful, ponders these changing conditions. Desirable things don’t charm the mind, undesirable ones bring no resistance”.

Participants were also given a hand-out listing seven mental qualities which support the development of equanimity, viz.

• Virtue, or integrity, enabling blamelessness

• Faith, or confidence, bringing a sense of assurance grounded in wisdom

• A well-developed mind, one that has cultivated calm, concentration and mindfulness

• A sense of wellbeing, by developing loving kindness

• Understanding, or wisdom, in particular the ability to separate people’s actions from who they are

• Insight, or seeing into the nature of things as they are, especially their impermanence

• Freedom, in the sense of letting go of reactive tendencies

INVESTIGATION & FINDINGS

First pair: Gain and Loss

(Win/Acquire/Profit : Forfeit/Deprivation/Grief)

The most obvious manifestation of this pair was seen in terms of material things, money or possessions, and the idea of acquiring and keeping what is “mine”, but it was also seen to relate to relationships and friendships.

It was noted that, in business dealings, ideas of “right” and “wrong” required skilful consideration before being translated into action. Ethical behaviour, while desirable can lead to attachment, while the ability to let go of losses in whatever form can help to avoid dwelling on past actions, often a source of lingering ill-will.

In family relationships, frustration can arise from the behaviour of those we care for, especially when help is offered but refused. Viewing the situation dispassionately and accepting the way it is, wisdom can arise. By gaining understanding one can lose worry.

In a different context, and reflecting a common tendency (among the British at least) to be affected by the external environment, seasonal changes were observed in terms of gain and loss, affecting mood and disposition both positively and negatively. Many thing are not within our control, but our attitude towards them is.

Two quotations from the Dhammpada are relevant:

“ ‘This is my child, this is my wealth’: such thoughts are the preoccupations of fools. If we are unable to own even ourselves, why do we make such claims?” (v.62)

“Contentment is the greatest wealth” (v.204)

Second pair: Status and Disgrace

(Fame/Reputation/Prestige : Shame/Obscurity/Disrepute)

Experiences here were often related to workplace situations – performance reviews, judgements being made of and by others, where the idea of one’s role or position can feel threatened or undermined. The challenge to maintain equanimity can be very strong here, especially where a sense of unfairness prevails.

Metta practice was found to be very helpful, indeed essential, to cope with the bad feelings that arise. Ideas of self-importance or vanity on the one hand or loss of self-esteem and worthlessness on the other can easily arise where one is pulled in either direction.

Although these situation can be very difficult, they can be eased with equanimity. Metta and compassion towards others who may be seen to contribute to one’s problems also helps.

Third pair: Praise and Censure

(Commendation/Reward/Admiration : Blame/Criticism/Reproach)

In some ways this is connected to status and disgrace, being related almost exclusively to opinions expressed by others in a judgemental way. Praise is pleasant to receive but there is a fine balance between skilful acceptance and unskilful attachment, i.e. wanting more. Blame is unpleasant when it is considered unjustified – or even when it is justified – but may be based in truth.

Luang Por Munindo, abbot of Ratanagiri Monastery in Northumberland, notes in his Dhammapāda Reflections, that “The Buddha was blamed and criticized just like everyone else. To seek only praise and fear blame is fruitless. The only blame with which we really need to be concerned is that which is offered by the wise.”

When we receive blame, therefore, the equanimous view is to consider (a) whether it is true or false and (b) where it comes from, and to try and respond with wisdom.

Another point made is that of self-blame, which is a form of ill-will. Making mistakes, having careless accidents, misspeaking and forgetting are everyday examples that most people can relate to, but the unskilfulness is compounded when self-inflicted accusations and recriminations follow. Mindfulness and metta are urgently needed here!

“I should/shouldn’t”, “I must/mustn’t” “I ought/oughtn’t” are powerful thoughts that arise from self-judgement, and which can only create additional suffering when applied critically. Resolving to avoid repetition is skilful only when accompanied by kindness towards ourselves.

Fourth pair: Pleasure and Pain

(Gratification/Success/Elation) : (Disappointment/Failure/Regret)

The teachings tell us that there are only three kinds of feelings: pleasant, unpleasant and neutral. In practice we tend to experience extremes, being elated or overjoyed by such things as new-born children or delight in relatives’ achievements, or in playing or listening to music, where it is easy to become “lost” in the experience.

In contrast, physical pain can require strong resolve to overcome. Bodily pain during sitting practice is quite common, especially among new meditators. Various solutions exist, from experimenting with posture and arrangements of cushions to preparatory physical exercises, and practising Tai Chi or Pilates. Patient persistence works better than grim endurance!

Visits to the dentist seemed to come up as a popular (or unpopular) examples, but on examination were often seen to be about the fear of pain rather than the pain itself. The quotation “Pain is inevitable, suffering is optional” has relevance, and can apply indirectly, for example in the distress caused by witnessing chronic physical pain suffered by loved ones.

Careful investigation can reveal that some pleasures and pains are the fruit of one’s actions, and again that impermanence applies here as in all things – all that arises will at some point cease.

CONCLUSIONS

Participant on the course presented their findings in various forms at the final meeting; some were given verbally, some written, some presented visually. They are summarised here:

• This course has helped me to understand myself and to be aware of the origin of different feelings that I have. I can put a name to these feelings and work to minimize the damage.

Also listening others’ experiences or feelings, that in many cases happen to me, it make me feel secure: "I am not the only one"

The big discovery has been equanimity, our protection in everyday issues, very helpful but as well very challenging.

• There is no right or wrong

There is only the skilful

I will do my best to walk the middle way

There is no good without evil

Evil must never be allowed to lead

To achieve this I will use my

Heart, mind, body and soul

There is

Praise yet Blame

Loss yet Gain

Pleasure yet Pain

Fame yet ill-fame

I am the wielder of these states

I accept that I cannot control all aspects

But I can control my response

As these come and go I will respect them in turn

I will greet each one

When they leave I will say farewell without clinging on

I continue to walk my path to my unknown future

I regret nothing as the path I have taken has taught me much

I can pass the baton of knowledge through time

I am truly grateful for what life has on offer

8 worldly winds

I am not free

I have more choice

• Success or calamity – find your balance with equanimity.

• A visual image came to mind, for which I drew a diagram. It took the form of a weighing scale with equanimity as the central balancing point, supported below by loving kindness, compassion and sympathetic joy. The eight worldly conditions can tip the balance either way if they are weighted by attachment, but acceptance can reduce this effect by removing some of the weight. The seven mental qualities act as counterbalancing forces.

• The lessons of the course for me were contained within a single activity, that of making a knitted doll for a young family member. Aiming to please, fearing disappointment, seeking perfection, worrying about failure, feeling satisfaction, self-judging, hanging on, letting go, all eight conditions were there!

• The value of the course has been in deepening my understanding of how the eight conditions arise and the realisation that I have a choice in the way I react to them. Mindfulness is the key to this. In dealing with other people, it was an important realisation that it is possible to separate the person from the words or actions, and that it helps in situations where criticisms or complaints are made not to take thing personally.

The course has begun to change my attitude in dealing with working relationships; where previously there was an inclination towards confrontation and conflict, now there is more acceptance, goodwill and compassion. The former gave rise to negativity, the latter has a more positive and more productive effect.

• I saw the eight worldly conditions visually and created a picture of a rolling wave pattern, with the peaks (represented in brighter colours) as the desirable conditions and the troughs (represented in plainer colours) as the undesirable ones. The Brahma Viharas run across the centre with equanimity highlighted as the inner strength that keeps us balanced in the middle of all that is. Below came the reminder: “All is inconstant, stressful and subject to change.”

• Working with young people, I notice how their modes of communication are highly influenced by graphical images created by modern technology. The emoji is a classic example of this, creating a kind of language of its own where ideas, feelings and meaning can be expressed simply, pithily and often amusingly. Finding suitable emojis and matching them to the eight worldly conditions helped create an overall picture that encapsulated the meaning of the sutta and provided a ready means of recalling the lessons of the course.

• A path of growing in wisdom

By nature everything is impermanent. The more we get drawn to feeling secure by holding on to things that are subject to change the more stressful our lives can become. At first this perception feels a bit scary. If I am not to be drawn to anything, what is the point of pleasure if I am not to be drawn to it, how do I embrace pain better without giving it my full attention?

In the discoveries experienced personally over the course of the last 6 weeks, I have found that the way to start developing a true happiness starts with metta. One can only really start appreciating the miracle that we exist in the first place by actually loving ourselves unconditionally. Once metta starts to develop, one is less tempted to get drawn in to coping strategies that are unskilful, stressful and subject to change. If one can observe a situation with skilful thoughts, without getting as emotionally involved, one can react accordingly. Self-appreciation with loving kindness then sharing that with others is mandatory for a healthy, happy balanced life. We are then less drawn to the 8 worldly conditions that are impermanent, stressful and subject to change.

The Metta Sutta

The Suttas, or discourses, formed the basis of the Buddha's teachings to his disciples. There are many thousands of them, some better known than others and some also known as Pali chants as well as written texts. One of the most popular chants at Samatha meetings is the Metta Sutta, which evokes the simple but powerful message of loving kindness, or well-wishing to all beings.

The translation below is taken from the Samatha Chanting Book (there are many different translations.) The Pali chant can be listened to via the 'Explore publications' page on this website.

Metta Sutta

He who is skilled in welfare, who wishes to attain that calm state (nibbana), should act in this way: he should be able, upright, perfectly upright, of noble speech, gentle and humble.

Contented, easily supported, with few duties, of simple livelihood, with senses calmed, discreet, not impudent, he should not be greedily attached to families.

He should not pursue the slightest thing for which other wise men might blame him.

May all beings be happy and secure, may their hearts be wholesome!

Whatever living beings there be: feeble or strong, tall, stout or medium, short, small or large, without exception; seen or unseen, those dwelling far or near, those who are born or those who are yet to be born, may all beings be happy!

Let one not deceive another, nor despise any person whatsoever, in any place. Let him not wish any harm to another out of anger or ill-will.

Just as a mother would protect her only child at the risk of her own life, even so, let him cultivate a boundless heart towards all beings.

Let his thoughts of boundless love pervade the whole world; above, below and across without any obstruction, without any hatred, without any enmity.

Whether he stands, walks, sits or lies down, as long as he is awake, he should develop his mindfulness. This they say is the noblest living here in this world.

Not falling into wrong views, endowed with sila and insight, by discarding attachments to sense desires, he never again knows rebirth.

Acknowledgement:

Peter Harvey, who provided some very helpful notes and references.

References and translations:

The Lokavipatti Sutta by Thanissaro Bikkhu, at www.accesstoinsight.org

Equanimity – seven mental qualities, by Gil Fronsdal at www.insightmeditationcenter.org